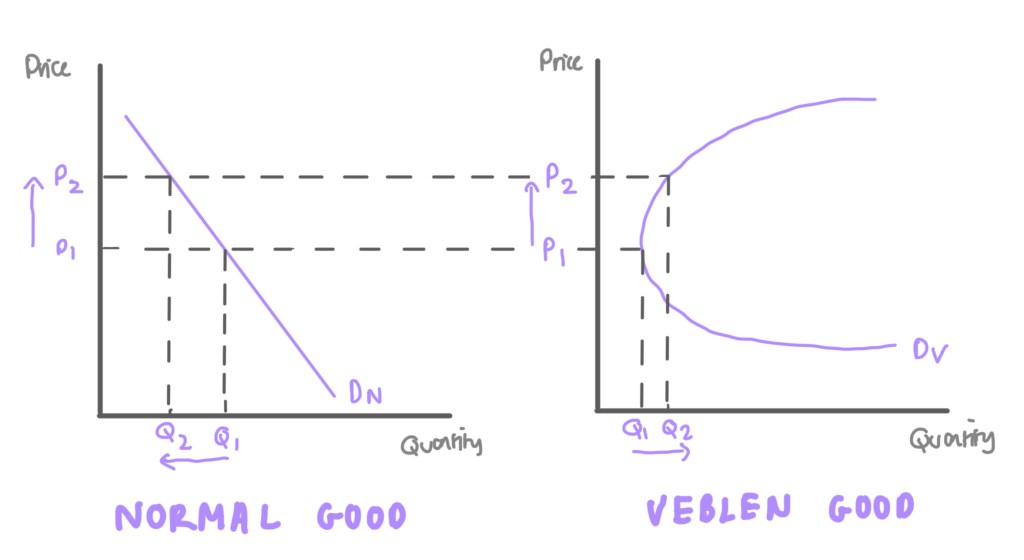

Supercars are a common form of Veblen Good which are goods and services that contradict the law of demand. A Veblen Good is defined by Thorstein Veblen as a good or service for which quantity demanded rises as prices rise. This phenomenon can be illustrated using the demand curves below. Both Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 have the same change in price, from P1 to P2 however for the normal demand curve (DN) this results in a decrease in demand from Q1 to Q2. For the Veblen demand curve DV this results in an increase in demand from Q1 to Q2.

The driving factor why supercars function as Veblen goods is due to conspicuous consumption, a form of status consumption where consumers purchase goods of higher price or quality than necessary to signal social and economic status (J. Phillips, 2014). In the case of supercars, the high price is not a direct reflection of functionality but serves as a symbol of success and economic power. As the price of a supercar increases, its exclusivity and therefore its value as a status symbol rises as fewer consumers can afford to purchase it. This is because supercars are positional goods which valued based on their distribution and supply within a society (Kenton, n.d.). This can be best summarised as saying ‘While any car can transport someone from point A to point B, a supercar does so while showing the affluence of the owner’ (J. Phillips, 2014). If the price of a supercar drops too low (as illustrated in Fig. 2 below P1), the vehicle loses its social status appeal, and demand begins to behave like that for a normal good.

For example, in Q1 2024, Volkswagen’s Sport Luxury Group (Porsche) achieved an average price per car of €114,704, while its core brands (Volkswagen, Seat, and Skoda) averaged just €27,494 (Volkswagen Group, 2024). Despite many shared components including the chassis in some cases, the Porsche brand charges a premium due to its perception as more exclusive and luxurious (Marriage, 2023). This reflects a form of confirmation bias, where consumer expectations about a brand’s luxury status allow firms to charge higher prices, reinforcing the perception itself. The Tesla Model 3 Performance goes from 0-60 mph in 2.9 seconds. The Audi R8 V10 goes from 0-60 mph in 3.1 seconds. Yet the slower car costs £100,000 used (Autotrader.co.uk, 2025) while the Tesla cost £59,000 new (Tesla, 2024). This is despite the fact the Tesla has more seats and arguably more comfort. Thus, price is a key driver of demand for supercars not due to practical considerations, but due to the social value conferred by ownership.

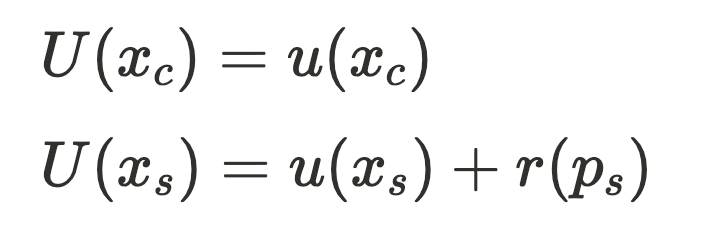

The concept of conspicuous consumption can also be illustrated mathematically.

For normal cars, U(xc) shows the utility function for xc units of cars being consumed, where the only utility (u(xc)) is intrinsic derived from the satisfaction the car provides to the consumer. However U(xs) shows the utility function for xs units of a supercars which contains intrinsic utility, u(xs) and status/relative utility, r(ps) which is dependent on the price of the supercar, ps. Status/Relative Utility is the utility gained by the consumer from the comparison of the supercar to other cars, which only has value if the supercar in question is better in some way than other cars. In this case the differentiator is price. This clearly shows why supercars are priced highly as the additional status utility gained by the supercar consumer is dependent on the price of the supercar.

This means higher prices will lead to higher utility for consumers encouraging firms to increase prices once again. This also illustrates the demand curve shown in Fig 2. above P1. This idea of status utility also links into Festinger’s Social Comparison Theory where consumers compare themselves to others to understand the value of items and themselves in absence of objective standards (McIntyre and Eisenstadt, 2011). Supercar consumers may use the price of their car compared to other’s cars in order to gain satisfaction from the social comparison using a definable metric. This means the price of supercars is also high in order for supercar consumers to their cars as a point of comparison to society

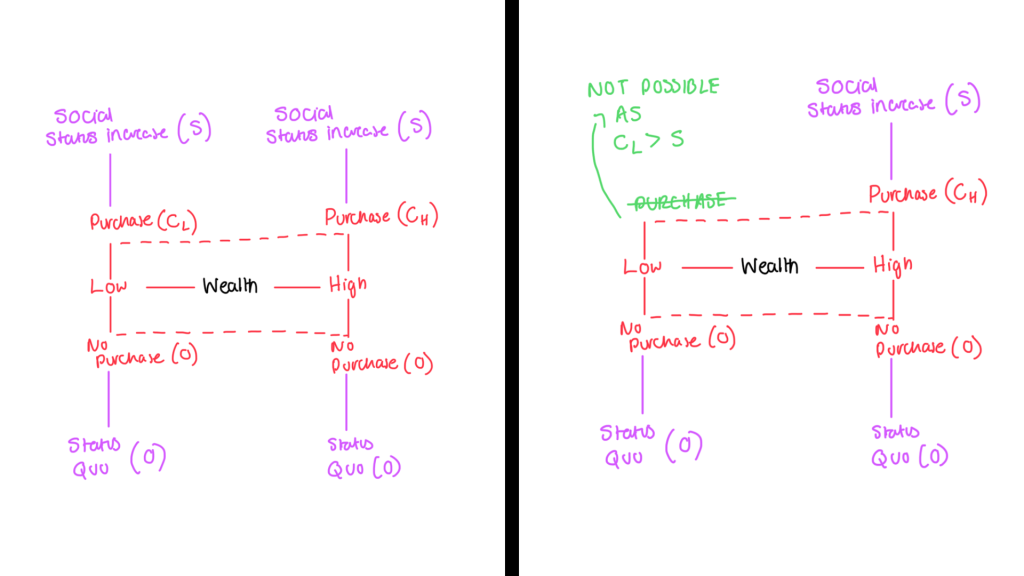

The status-signalling aspect for the purchase of supercars and its high price tag justification can also be illustrated by using a simple signalling game.

The signalling game above in Fig 4. shows two types of initial player (Player 1), with either low or high wealth hidden (shown by the dashed lines) from Player 2 (Society). The cost for not purchasing the supercar is 0 and the payoff is simply status quo social status. The cost of purchasing the supercar is CL for Low Wealth Player 1 or CH for High Wealth Player 1’s. The payoff for purchasing the supercar is S (status utility). This is because the purchase of the supercar signals to Player 2 (Society) that Player 1 is possibly from high wealth and therefore increased social status is awarded leading to S. However the option for purchase for lower wealth players must not be available as both types of players would simply purchase and claim S and therefore there would be no credible signal for Player 2 to discern whether Player 1 is wealthy or not. Therefore supercars must be expensive enough for CL > S > CH to be true. Fig. 5 shows this scenario which enables society to see the player that purchases the supercar as wealthy as this is a credible signal as only if Player 1 is wealthy can they afford the car. Thus in order for differentiation and signalling to be effective, supercars must be expensive.

However, the size of the payoff of S may change in certain conditions. Depending on the culture of the regions where the supercar is purchased the payoff may be larger or smaller in accordance. For example, in Scandinavia the culture and design of society is much more low-key, minimalist and less flashy (Kliest, 2024). Therefore, the payoff for a supercar purchase will be lower in Scandinavia as Player 2 values supercar prestige less relative to other regions. The opposing case can be made for Dubai, where some consumers wrap their vehicles in solid gold to further show their wealth (PropertyStellar, 2025). Here the payoff may be larger than in other regions due to the much more material culture. However it may be argued that the cost CH may also be much higher as there is a greater concentration of wealth relative to other regions so status utility is not as easily gained.

Therefore, the high price of supercars can be explained through conspicuous consumption and signalling by consumers. This enables supercars to be Veblen goods and encourage firms to charge high prices.

Leave a comment